In 2006, “our guys in Pennsylvania, Virginia, Rhode Island, Missouri, Montana and Ohio could never move their numbers, and in the last couple of weeks the races blew open,” said Billy Piper, chief of staff to Sen.

A half-dozen senators fighting for their political lives — and their party’s hold on the majority — in tough races while trying to avoid being dragged down by an unpopular president and the stark reality that second-term midterm elections almost never work out for the side controlling the White House.

2014? Yes — but also 2006, an election cycle that Republicans are increasingly beginning to see as a parallel to this one as the fight for control of the Senate enters its final four weeks.

“During that cycle, our guys in Pennsylvania, Virginia, Rhode Island, Missouri, Montana and Ohio could never move their numbers, and in the last couple of weeks the races blew open,” said Billy Piper, who was chief of staff to Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) at the time. “The macro environment was too much to overcome in states that were not reliably red.”

At the start of the 2006 election, Republicans controlled 55 seats, buoyed by two consecutive elections — 2002 and 2004 — that had moved seats their way. But their vulnerabilities were significant. Despite defending only 15 seats (to the Democrats’ 17), the GOP had incumbents in Pennsylvania and Rhode Island — two states that President George W. Bush had lost convincingly two years earlier — as well as sitting senators in places such as Missouri and Montana who, through a combination of the competitiveness of their states and their own foibles, were in deep trouble. As the cycle wore on, Sen. George Allen (R-Va.) turned his race ultra-competitive by referring to a Democratic tracker as a “macaca.”

By this time in the 2006 election, it had long been clear that Sen. Rick Santorum (R-Pa.) wasn’t going to make a miraculous comeback against Bob Casey Jr. (D), who had led the incumbent by double digits throughout the campaign.

But the other five incumbent races, in which GOP senators such as Jim Talent (Mo.) and Lincoln Chafee (R.I.) had managed to stay in the hunt — started to turn south for Republicans.

The main factor was the deep unpopularity of Bush, who sat at 37 percent nationally. That distaste for the head of the Republican Party made Democratic messaging easy: Don’t like President Bush? Send him a message by voting against the person who has voted with him [fill-in-the-blank-but-it’s-a-lot percentage] of the time. Bush stayed largely hidden on the campaign trail, but it didn’t matter.

Sen. Mike DeWine (R-Ohio) collapsed, losing to Sherrod Brown by 15 points. (Side note: When you lose by that much, it’s hard to blame Bush or the national environment totally for the loss.) Chafee’s race also turned permanently against him — Bush had won only 39 percent of the vote in Rhode Island — and Sheldon Whitehouse won by seven points.

Then there were the trio of Republican incumbents who lost by two points or less: Allen (a 0.3 percentage point loss), Talent (2.1 points) and Sen. Conrad Burns of Montana (0.7 points). In all three cases, the incumbents remained stuck in the mid to upper 40s, the spot where they had been for much of the election — and lost as undecided voters flocked to their opponents.

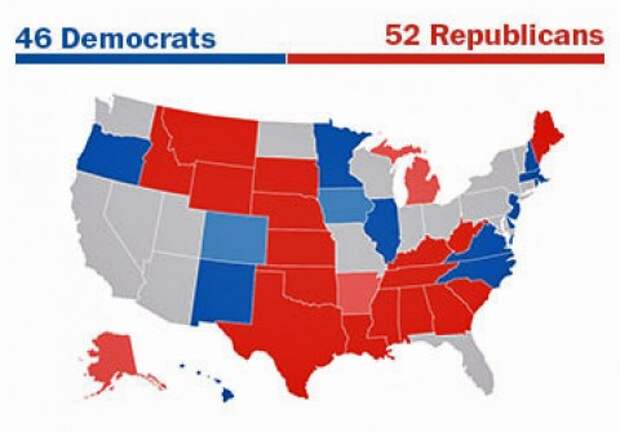

It all added up to a six-seat loss for Republicans and the minority status in the Senate, defeats that came just two years after a Republican president was reelected for the first time in about two decades. And it meant that Republicans spent the next eight years — all the way through today — in the minority.

The similarities between the 2006 and 2014 midterms are striking.

Like Bush, this is the second midterm election of Obama’s presidency. Like Bush, Obama is not at all popular nationally. (Gallup’s daily tracking puts his job approval rating at 41 percent.

Like Republicans in 2006, the fate of Democratic control rests in the hands of a handful of incumbents — Sens. Mark Pryor (Ark.), Mark Begich (Alaska), Mark Udall (Colo.), Mary Landrieu (La.) and Kay Hagan (N.C.) — who sit in states that, at best, swing between the two parties and, at worst, are firmly Republican at the presidential level.

And in each of the five races, the Democratic incumbents have spent much of the past 22 months successfully fighting against the negative pull of their national party — making the case that voting for them has little to do with supporting (or not) Obama.

Of late, however, the movement has been all toward Republicans. Polling averages show Pryor down to Rep. Tom Cotton (R) and suggest that Landrieu has little hope of getting the 50 percent she needs on Nov. 4 to avoid a politically treacherous runoff on Dec. 6.

In Alaska, former state attorney general Dan Sullivan (R) has led Begich in the past six polls, a major change from even a few months ago, when the incumbent had looked strong. Ditto in Colorado, where Rep. Cory Gardner (R) has caught — and, in some polls, passed — Udall after spending months running behind.

Only Hagan appears, at the moment, to be immune from the negative gravitational forces on her party. She led state House Speaker Thom Tillis (R) by four points — 44 percent to 40 percent — in an NBC/Marist poll released Sunday morning. Hagan’s resilience may be due, at least in part, to Tillis’s role as the leader of a controversial state legislature that passed a number of conservative agenda items in recent years.

The question in the final four weeks of the campaign is whether these Democratic incumbents can find a means to reverse the effects the national environment is having on their races in ways that the 2006 Republicans couldn’t.

Obama did them no favors Thursday when, in a speech at Northwestern University, he said: “I am not on the ballot this fall. . . . But make no mistake: These policies are on the ballot. Every single one of them.”

Democrats who want to hold the Senate majority better hope voters don’t agree.