Gwen Graham is the Democratic challenger in Florida's Second Congressional District. Analysts have called the contest a “tossup,” one of about 15 in the nation.

Among the rolling hills and Spanish moss of Florida’s panhandle, voters have long demanded that politicians walk a wobbly tightrope between the two dominant political parties: Lean too far one way and a tumble is all but certain.

Navigating that kind of crossing in this part of Florida, which looks to the South for cultural kinship but still has a solid core of Democratic-leaning voters, is particularly treacherous these days. More than two dozen Blue Dog House Democrats, a near-extinct group of socially moderate, fiscally conservative lawmakers, have been defeated by Republicans or left office since 2010. The congressional district here, Florida’s Second, has followed that pattern: Four years ago, Representative Steve Southerland II, a political novice backed by the Tea Party, defeated a longtime moderate Democrat.

But in an election season full of dire predictions for Democrats, the party is pinning one of its few genuine chances to reclaim a House seat on a little-known northwest Florida woman with a well-known name. Voters know her just as Gwen, but it is her last name, Graham, that resonates — a marquee Florida brand brimming with centrist political currency. And her father, Bob Graham, who was a popular longtime United States senator and governor, is usually by her side these days, chewing on pork at a fund-raiser, gobbling peanuts at a rally and extolling his eldest daughter’s pledge to put people before party as a Graham Democrat.

The latest news, analysis and election results for the 2014 midterm campaign.

“If we had 50 Gwen Grahams in the United States Congress, it would be a different United States Congress,” Mr. Graham said at a recent Democratic barbecue in this rural city. “Washington needs more women. Washington needs more women like Gwen Graham.”

In a district that until 2010 had not elected a Republican for more than a century, her gilded family name has allowed Ms. Graham, 51, to raise more money than the incumbent, a rarity, and to use it to run television political ads as early as June.

“He has turnout in his favor,” Fred Piccolo Jr., a Republican political consultant, said of Mr. Southerland. “But she has taken the confluence of name and the ability to raise money and the automatic gravitas that comes with that and parlayed it into a smart message.”

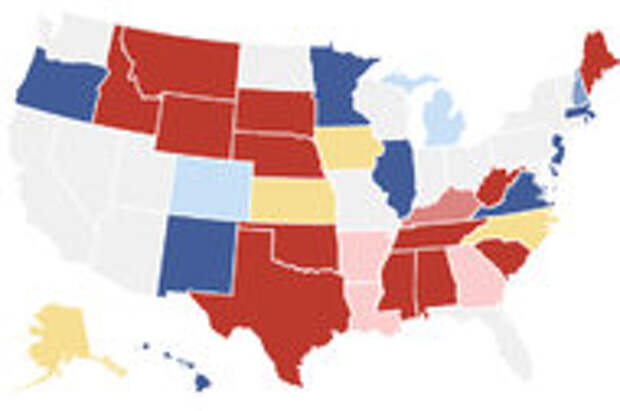

Congressional analysts have called the contest in this district, running from Tallahassee west to Panama City, a “tossup,” one of about 15 in the country.

But Mr. Southerland, the 49-year-old co-owner of his family-run funeral home chain who co-founded a Panama City Tea Party group, has three powerful forces on his side: voters’ antipathy to President Obama, their deep-rooted opposition to his Affordable Health Care law and the growing inclination to vote Republican.

“I’ve been a Democrat for 50-something years,” said Mike Castleberry, a Southerland supporter, as he walked to his car at a Walmart here. “But in 2008, I realized I had nothing in common with what they are promoting.”

A few miles away in the historic downtown section, Alane Prinz, who owns a children’s clothing store, railed against the health care law. She is still impressed by Mr. Graham. “Years ago, I loved him,” she said. But, she added, “I’m not so sure about her.”

Ms. Graham is attempting to unseat Representative Steve Southerland II. Credit Andrew Wardlow/The News Herald, via Associated Press

In recent weeks, Mr. Southerland has ratcheted up his campaign, increasing his fund-raising and running a spate of advertisements that tie Ms. Graham to Mr. Obama; the House minority leader, Nancy Pelosi; and the health care law. Mr. Southerland also portrays Ms. Graham, who traded a law career to stay at home with her three children and eventually work as a school district administrator in Tallahassee, as a candidate who does not represent North Florida values, is less moderate than she claims and shrugs off job creation.

“People want to be rewarded for their work and their labor,” Mr. Southerland said in an interview. “They feel that right now the federal government has encroached upon that ability.”

“This is a Democratic economy,” he added. “And they are going to have to own it.”

But some political analysts said Mr. Southerland had run a relatively lackluster campaign marked by a series of missteps that Ms. Graham has deftly used against him, particularly with female voters, a crucial constituency. Mr. Southerland complained that his salary, $174,000, considerably steeper than the wages of most people in his district, was not that high, considering the risks of the job and the loss of his business income. He also led the charge to toughen the food stamp program.

More recently, supporters sent official campaign invitations for an all-male private fund-raiser for Mr. Southerland that harked back to “the 12th century with King Arthur’s Round Table.”

“Tell the Misses not to wait up,” the invitation read, “because the after dinner whiskey and cigars will be smooth & the issues to discuss are many.”

Asked by the press last month to comment on the invitation, Mr. Southerland, who said he had not seen it, replied: “Listen, has Gwen Graham ever been to a lingerie shower? Ask her. And how many men were there?”

Adele Graham showed her support for her daughter Gwen with a decorated dress at a barbecue fund-raising event in Marianna. Credit Emily E. Fox for The New York Times

In a recent interview, he emphasized that he is surrounded by five women — four daughters and a wife. “They know that women have no stronger supporter than me.”

Some voters have dismissed the hubbub as politics as usual. But Ms. Graham and her supporters have pilloried him for his statement and his stance on women’s issues, in general, including a vote against the Violence Against Women Act and equal pay for women.

“This whole thing felt very ‘Mad Men’-ish to me,” Ms. Graham said. “It’s a demeaning response to women and indicative of his worldview.”

Ms. Graham, a self-described “glass half-full” person and mother of three adult sons, said she decided to run last year after she got fed up with Congress’s inability to function. She contrasted that with what she described as her father’s ability to find common ground with Republicans and not demonize his opponents.

“I have the ability to look at the issues from a neutral position and talk to both sides,” Ms. Graham said. “Compromise means that you are not going to get everything you want.”

Despite the district’s location, demographics are on her side. There are more registered female voters than male, and more Democrats than Republicans, although some wear the label so lightly that they seldom vote for Democrats. The vote is often split: Republicans for president and Democrats for Congress and local offices. Alex Sink, a Democrat, won the district in her unsuccessful campaign against Gov. Rick Scott in 2010.

What’s more, Ms. Graham’s anchor is Leon County, which includes the capital, Tallahassee. It is a city loaded with professors, students and African-Americans who skew left and government workers, some of whom do not look kindly on Mr. Southerland’s 2013 vote to shut down the government. Leon County makes up more than 40 percent of the 14-county district.

The political landscape grows less hospitable for Ms. Graham the farther west one travels. But even in towns like this, she has supporters, particularly among women and African-Americans.

David Wasserman, who analyzes congressional races for the Cook Political Report, said that to win Ms. Graham needed to woo the conservative Democrats who voted for Mr. Southerland in the past two elections.

“Southerland could still be rescued by the partisan leanings of the district,” he said. “But if Democrats were to lose this race, it would be terribly demoralizing for their party after nominating such a strong candidate.”